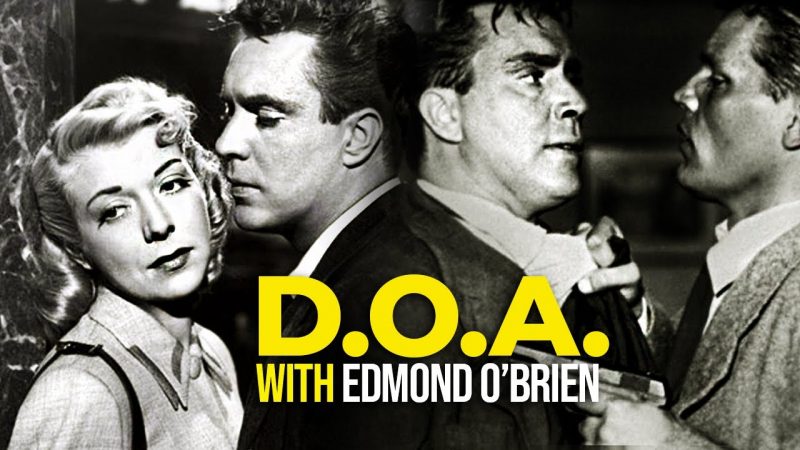

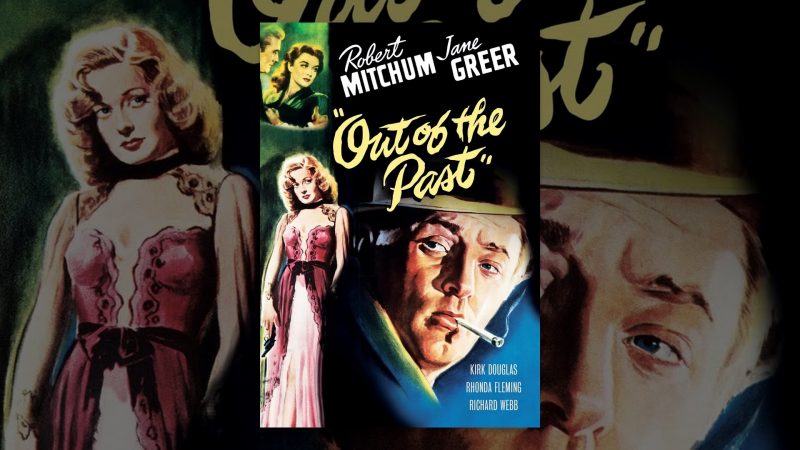

Though it is not without its flaws, the movie D.O.A. (1950) is considered by many to be one of the best examples of classic film noir. When I first started watching old movies, I didn’t watch much film noir, however after watching and enjoying movies like Scarlet Street, Woman in the Window, and Out of the Past among others I developed a new appreciation for the style. Now I am on a quest to learn as much as I can about it and add many more to the list of those I’ve already watched.

Category: <span>Film Noir</span>

“I never told you I was anything but what I am. You just wanted to imagine I was.”

That claim, uttered by Jane Greer as the devious Kathie Moffat in director Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, is not entirely true. The character is an exercise in self-construction, spending much of the film behind an array of masks designed to please whichever man she is trying to manipulate at the time. But at heart, she is far from pleasing, for Kathie is undiluted feminine poison, crossing, double-crossing, and triple-crossing everyone unlucky enough to come into contact with her. By turns innocent and evil, virtuous and dishonest, she operates entirely without moral compass or conscience to guide her, and in the process she destroys not only herself, but all of the men in her orbit.

Enduring Appeal of a Film Noir Classic

Stuart Heisler’s adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel still influences Hollywood, with a tale of dubious alliances and loyalty.

In The Glass Key, Alan Ladd plays Ed Beaumont, right-hand man to Paul Madvig (Brian Donlevy), a boorish, ambitious player with political aspirations. When the murder of a reckless playboy casts suspicion on his boss, Ed works to protect Madvig. Matters are further complicated when Madvig falls for the daughter of a wealthy industrialist (Veronica Lake) – especially when Ed falls under the spell of the same girl.

Dad of TV’s Bewitched Star Enjoyed Diverse Career as Actor, Director

The ambitious light leading man Robert Montgomery fought his own typecasting — eventually proving himself a creative force in movies, on stage, and in television.

Too often these days, Robert Montgomery is remembered primarily as the father of Elizabeth Montgomery, the glamorous actress who played Samantha Stevens on TV’s Bewitched for nine seasons.

In fact, Robert Montgomery may be the most accomplished Hollywood star you’ve never heard of. He started out playing rich boys, but fought for diverse roles, eventually winning acclaim behind the camera and as a Tony-winning Broadway director.

Humphrey Bogart & Lauren Bacall in Noir Mystery

Quite often referred to as the quintessential film-noir, The Big Sleep stars Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in a gripping, feisty murder mystery.

PI Phillip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart) is called in to investigate the bribery and blackmail of a young rich girl, Carmen Starkwood (Vickers) – and the actions of both her and her sister Vivian (Lauren Bacall) lead Marlowe’s investigative mind to discover a far bigger and more complex series of manipulations beneath the surface.

Classic Humphrey Bogart Detective Story Regarded as First Film Noir

The Maltese Falcon marked the auspicious directing debut of John Huston, who also wrote the screenplay and was blessed with an exceptional cast of superb players.

Huston’s film was actually Warner Bros.’ third adaptation of the 1930 Dashiell Hammett novel. The first, in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and Bebe Daniels in the lead roles of detective Sam Spade and femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy (called Ruth Wonderly throughout). In 1936 came a poor (and thinly disguised) remake called Satan Met a Lady with the hammy, unreal Warren William and a comedic Bette Davis.

Dick Powell Reinvented Himself Playing Detective Philip Marlowe

Murder, My Sweet is a masterful early film noir, a brilliant mix of convoluted plot, hard-boiled dialogue, nightmarish atmosphere, and comically cynical narration.

This is the 1944 movie in which Dick Powell reinvented himself. With it, Powell forever buried his screen image of an overgrown crooner — one built in frothy Warners musicals of the 1930s.

Dick Powell did it by convincing a dubious world he could play a hardened, complex tough-guy detective.

Dark Passage (1947), a back alley plastic surgeon tells Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart), “There’s no such thing as courage. There’s only fear, the fear of getting hurt and the fear of dying. That’s why human beings live so long.” He is  looking straight at Parry and — through the use of the subjective camera — straight at the audience. His statement is especially striking because it dismisses courage as a myth soon after World War II, rejecting a basic cultural belief that all of America and all of Hollywood had just spent four years trying to build up. Such an attack on society’s (and Hollywood’s) most cherished values is characteristic of film noir, and perhaps its favorite target is the most fundamental value of all — the family.

looking straight at Parry and — through the use of the subjective camera — straight at the audience. His statement is especially striking because it dismisses courage as a myth soon after World War II, rejecting a basic cultural belief that all of America and all of Hollywood had just spent four years trying to build up. Such an attack on society’s (and Hollywood’s) most cherished values is characteristic of film noir, and perhaps its favorite target is the most fundamental value of all — the family.

Film noir began to take shape just before the United States entered World War II with films such as Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), I Wake Up Screaming (1941), and The Maltese Falcon (1941), but it did not develop fully until the late stages of the War and flourished in the immediate post-War years. Since noir films generally question social and governmental institutions, it seems likely that wartime pressure to represent the United States and American society in a positive light and to keep up the people’s spirits prevented Hollywood from exploring the darker aspects of noir while the outcome of the War was still in doubt.

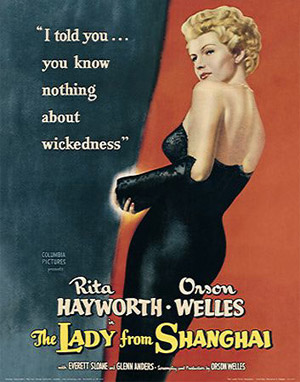

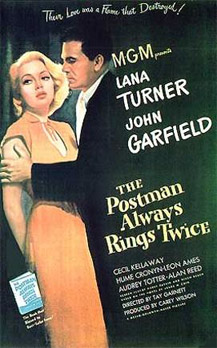

Many critics have argued convincingly that film noir follows much the same pattern of rewarding “good” women and punishing “bad” women as conventional Hollywood films. The rewards and punishments for women (and men) in film noir are especially serious — characters who willingly play their proper roles tend to survive beyond the end of the film, while characters who resist playing these roles often die violently or, less commonly, go to jail. On rare occasions, these films even deliver a Hollywood happy ending, when a family or a relationship that was threatened or torn apart during the course of the film actually is restored in the final scene. Meanwhile, critics who find a conservative message in film noir point out that these films endorse the family not only in their narrative content but even in their visual style, which creates a negative contrast between the noir world and the world of traditional family life.

Film noir‘s subversive view of family life and women’s accepted role in society extends to its portrayal of the “good” or “normal” woman. The good woman embraces her traditional “place” in the family, but she is out of place in film noir. Although she offers the hero a chance to escape from the sexy, destructive femme fatale and the dangerous noir world, the good n proves to be a mirage that the hero cannot reach. She functions as a foil for the femme fatale, not as a realistic alternative or a prescription for female behavior. Indeed, Janey Place argues that “the lack of excitement offered by the safe woman is so clearly contrasted with the sensual, passionate appeal of the other that the detective’s destruction is inevitable.” 38 Ultimately, the good woman suggests that society’s prescription for happiness, the traditional family, is uninteresting and unattainable. The world of the good woman and “normal” family values contrasts sharply with the dominant world of film noir in both visual style and narrative content, as if the cultural ideal of family life — the dominant image of most Hollywood films at the time — is a mere fantasy for the noir characters. In film noir, the American dream is indeed a dream. The good woman often lives in an idealized country setting or in a well- kept apartment, outside of the dark, rain-soaked urban streets associated with the noir world. She is filmed using the visual techniques of classical Hollywood cinema: high-key lighting, eye-level camera angles, and open spaces — free of the disturbing mise-en-scène that surrounds the femme fatale. 39 And she remains passive, nurturing, and non-threatening — a redeeming angel for a hero hopelessly tempted by the active, independent, and dangerous femme fatale. 40