Dark Passage (1947), a back alley plastic surgeon tells Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart), “There’s no such thing as courage. There’s only fear, the fear of getting hurt and the fear of dying. That’s why human beings live so long.” He is  looking straight at Parry and — through the use of the subjective camera — straight at the audience. His statement is especially striking because it dismisses courage as a myth soon after World War II, rejecting a basic cultural belief that all of America and all of Hollywood had just spent four years trying to build up. Such an attack on society’s (and Hollywood’s) most cherished values is characteristic of film noir, and perhaps its favorite target is the most fundamental value of all — the family.

looking straight at Parry and — through the use of the subjective camera — straight at the audience. His statement is especially striking because it dismisses courage as a myth soon after World War II, rejecting a basic cultural belief that all of America and all of Hollywood had just spent four years trying to build up. Such an attack on society’s (and Hollywood’s) most cherished values is characteristic of film noir, and perhaps its favorite target is the most fundamental value of all — the family.

A short description of film noir

In classical Hollywood cinema, as in American culture generally, the family and home life are celebrated as a safe haven from the world outside and a common aspiration of each generation. When we say that a film has a “happy ending,” we often mean that the male hero and his female love interest are united in marriage — or seem to be headed in that direction — before the closing credits. Indeed, many of the most popular films of the 1930s and ’40s depict the family almost as a cure-all that will save the hero from any trouble, if he or she can only learn to appreciate it. Thus, Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939) runs away from home, but discovers in the end that “There’s no place like home”; George Bailey in It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) nearly attempts suicide, only to find that friends and family make any crisis worth living through; and even Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind (1939) comes to value Tara, the family home, above all other things.

World War II only intensified American culture’s endorsement of society’s dominant ideology and the importance of shared values — values that may be said to begin with the “traditional” nuclear family. The urge to affirm marriage and the family, already a popular and therefore profitable formula for filmmakers before the War, became an absolute political and cultural imperative during the War years. As the War came to an end, however, films began to

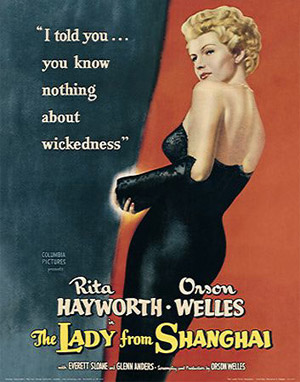

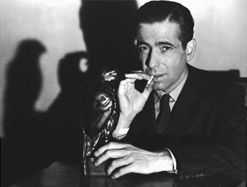

experiment with alternative formulas and introduced a radically different visual and narrative style. This body of films, which is generally thought to begin with The Maltese Falcon (1941) and end with Touch of Evil (1958), became known as film noir for its dark, disturbing visual style and thematic content.Of course, film noir confronts a range of status quo values and institutions and does not focus exclusively on the family. In many of these films, the criminal justice system is incompetent,1 the white-collar office is dull and dehumanizing,2 the police force is corrupt,3 and even the federal government is threatening and oppressive.4 Yet, like classical Hollywood cinema, film noir often expresses its view of American society through the image of the family generally and specifically woman’s place in the family. Dana Polan suggests that in mainstream Hollywood films, “realizing one’s place can only mean realizing one’s place in the family. . . . Family and public ideology are indeed one.”5 Sylvia Harvey elaborates on this viewpoint, tracing the complex connections between the depiction of women, family, and society on film:

All movies express social values, or the erosion of these values, through the ways in which they depict both institutions and relations between people. Certain institutions are more revealing of social values and beliefs than others, and the family is perhaps one of the most significant of these institutions. For it is through the particular representations of the family in various movies that we are able to study the process whereby existing social relations are rendered acceptable and valid.6

Harvey emphasizes the special function that women perform in communicating American culture’s view of the family: “[T]he representation of women has always been linked to this value-generating nexus of the family. . . . Woman’s place in the home determines her position in society, but also serves as a reflection of oppressive social relationships generally.”7

In film noir, women serve to express these films’ skepticism toward the family and the values that it supports. With few variations, noir films divide women into three categories: the femme fatale, an independent, ambitious woman who feels confined within a marriage or a close male-female relationship and attempts to break free, usually with violent results; the nurturing woman, who is often depicted as dull, featureless, and, in the end, unattainable — a chance at conventional marriage that is denied to the hero; and the “marrying type,” a woman who threatens the hero by insisting that he marry her and accept his conventional role as husband and father. Each type of film noir woman functions in a way that undermines society’s image of the traditional family.

Still, noir films usually stop short of rejecting the family altogether. While criticizing the family and marriage in a fairly overt way, film noir cannot resist the urge to restore or reinforce the family, even if it is only at the last minute. This restoration involves punishing or destroying women (and men) who transgress the boundaries of “normal” family relations or providing a tacked-on “happy ending” in which the hero marries the nurturing woman or even a converted femme fatale who has learned to accept her proper role. In either case, the ending contradicts the content and style of the film itself.

Thus, film noir inverts the classical Hollywood formula of wish fulfillment through the family and marriage — where marriage is the “happy ending” that resolves all conflicts — by denying such an ending or by providing a conventional happy ending that draws attention to itself as unrealistic or inappropriate in the context of a particular film. Indeed, either type of noir ending — the denial of marriage or the unrealistic happy ending — can be seen as a critique of classical Hollywood cinema and the traditional values that it reinforces.

Be First to Comment