Contents

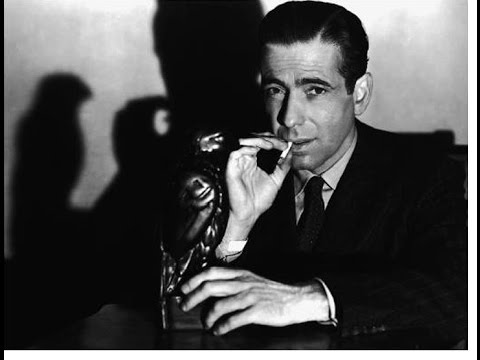

Classic Humphrey Bogart Detective Story Regarded as First Film Noir

The Maltese Falcon marked the auspicious directing debut of John Huston, who also wrote the screenplay and was blessed with an exceptional cast of superb players.

Huston’s film was actually Warner Bros.’ third adaptation of the 1930 Dashiell Hammett novel. The first, in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and Bebe Daniels in the lead roles of detective Sam Spade and femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy (called Ruth Wonderly throughout). In 1936 came a poor (and thinly disguised) remake called Satan Met a Lady with the hammy, unreal Warren William and a comedic Bette Davis.

Huston’s Film a Masterpiece

But Huston’s Falcon is the definitive version. It consistently hits just the right notes, has the most effective cast, Huston’s sparkling screenplay, and a moody atmosphere (by cinematographer Arthur Edeson) that anticipated the film noir genre by several years.

In San Francisco, private detectives Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) and Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) are approached by the sexy, frightened Miss Wonderly (Mary Astor). She engages them to track a man named Thursby. The lecherous Archer winds up murdered — shot to death by an unseen assailant on a hillside at Bush and Stockton streets. (In present-day San Francisco, a real-life marker honors the location of this fictional murder.)

In San Francisco, private detectives Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) and Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) are approached by the sexy, frightened Miss Wonderly (Mary Astor). She engages them to track a man named Thursby. The lecherous Archer winds up murdered — shot to death by an unseen assailant on a hillside at Bush and Stockton streets. (In present-day San Francisco, a real-life marker honors the location of this fictional murder.)

Spade spends a good part of the film trying to learn who killed three people — his partner Archer, Thursby and, later, a merchant mariner, Capt. Jacobi — while trying to unravel the mystery of a 16th-century figurine.

Sydney Greenstreet a Memorable “Fat Man”

Along the way he meets the sinister homosexual Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), the cheerfully dangerous “fat man” Casper Gutman (then-61-year-old Sydney Greenstreet, in his Oscar-nominated film debut) and Gutman’s callow “gunsel” Wilmer (Elisha Cook Jr., in a career-making role). He also must fend off suspicious police detectives Dundy (Barton MacLane) and Polhaus (Ward Bond).

In Spade’s corner is his trusty secretary Effie (Lee Patrick). He also must deal with his one-time mistress Iva Archer (Gladys George), who just happens to be the widow of his murdered partner.

The story is a stew — but that’s by design. As critic Danny Peary has observed, “I am sure that part of the reason this film has such a strong cult is that the story is so muddled that you can’t remember from one viewing to the next exactly what happens — so it’s always like new.” (Cult Movies, by Danny Peary, Dell Publishing, 1981)

Script Gives Sam Spade Character Memorable Lines

Falcon‘s Oscar-nominated script has line after line of memorable dialogue and one-liners which helped establish the conventions of film noir, itself the cinematic offspring of the 1920s and ’30s pulp fiction.

Some examples:

Spade, in a jocular toast with suspicious police detectives: “Success to crime.”

Space, after smacking the whiny, ineffectual Cairo: “When you’re slapped, you’ll take it and like it.”

When Cairo complains to Spade, “You always have such a very smooth explanation ready,” the detective responds, “What do you want me to do? Learn to stutter?”

Spade to his loyal secretary, Effie: “You’re a good man, sister.”

Spade to the murderous Brigid in the film’s penultimate scene, when he finally squeezes the truth out of her: “Well, if you get a good break, you’ll be out of (the women’s prison at) Tehachapi in 20 years and you can come back to me then. I hope they don’t hang you, precious, by that sweet neck.”

And perhaps, most famously, Spade to Det. Polhaus on what the Maltese falcon figurine really represents: “The stuff that dreams are made of.”

“Bogie” Character Established in Falcon

The Maltese Falcon marks the birth of the “Bogie” persona — the screen image Humphrey Bogart carried with him through countless Warners films of the 40s and which reached its full flower the following year in Casablanca. Sam Spade begins the Bogie tradition of an adaptable, self-reliant loner with his own codes of honor and conduct. He’s hardened, ironic, and beneath a veneer of cynicism, he frequently tries to do the right thing.

Here, the archetype is just in development. Spade retains his inconsistencies from Hammett’s novel: he’s both heroic in trying to get at the truth (and refusing to be bribed by Gutman) and amoral (he has an affair with his partner’s slutty wife, then discards her).

The film also takes a practical approach to depict gays. In the novel, Joel Cairo clearly is gay; here he is fey and fussy and described suggestively by Effie as smelling like gardenias. In 1941 Hollywood, was the closest you could get to labeling a character as gay.

Greenstreet, Lorre, Cook in Standout Supporting Roles

Among the outstanding supporting cast, several players stand out:

British-born stage veteran Sydney Greenstreet was 61 when he made his feature debut in this film as the loquacious, obsessive and dangerous Gutman. His remarkable voice, with its odd speech patterns and vocal dropoffs, add to Gutman’s mystery; you have to lean in to hear him better — and suddenly he’s got your rapt attention.

Sadly, Greenstreet’s film career covered only eight years and 23 roles. Eight of his films had him working with the superb Peter Lorre, who steals many moments here as Cairo.

(Interestingly, according to movie website imdb.com, the rotund Greenstreet partially inspired the appearance of the blobby Jabba the Hut in the Star Wars series.)

Elisha Cook Jr. gets a lot of mileage from the role of the immature “gunsel” Wilmer — his odd tics and mannerisms finding their way into many of his subsequent roles. As such, Cook owed a good chunk of his career to this film.

Ironically, Cook was miscast. Wilmer was supposed to be about 20, but Cook was 37 when Falcon was shot — and looked it.

Surprise Cameo by Another Huston

John Huston also managed to sneak a very famous actor into the film: his father. The legendary Walter Huston plays the mortally-wounded Capt. Jacobi, who, in his brief, nearly wordless appearance, delivers the falcon to Spade before dropping dead on a couch. It’s a nice touch — son saluting father, and father helping son in the latter’s first directing assignment.

The Maltese Falcon is a landmark film on so many levels. But beyond that, this Best Picture nominee endures simply because it is a good story, well told.

Be First to Comment