Contents

While screenwriters and directors are a movie’s first and second storytellers, editors are the third ones. Since editors are given a limited amount of footage, it may not appear so. Still, through editing techniques, the editor may construct or deconstruct a narrative or documentary and shape it to his or her own will.

“For a writer, it’s a word. For a composer or a musician, it’s a note. For an editor and a filmmaker, it’s the frames. The one frame off, or two frames added, or two frames less… it’s the difference between a sour note and a sweet note. It’s the difference between a clunky clumsy crap and orgasmic rhythm.” – Quentin Tarantino on film editing

The job of an editor constitutes much more than cutting and splicing footage. Walter Murch, the acclaimed Academy-Award-winning editor and sound designer, whose body of work includes The English Patient (1996) and The Godfather (1972), opens his book In The Blink of An Eye by sharing his nightmarish experience while editing Apocalypse Now (1979).

In that picture, Murch faced an intimidating 95:1 ratio, meaning that for every minute of the footage used in the final cut of the movie, there were 95 minutes not used. Thus, since Apocalypse Now’s theatrical release runs for 153 minutes, the total footage was about 14535 minutes or 242 hours long! With that abnormally extravagant quantity of footage, Murch’s primary task of scrutinizing the footage to determine what worked and what didn’t was exponentially bigger. All editors go through this same process but in a minor scale.

Ellipsis

Ellipsis is both a narrative device and the most basic idea in film editing. Ellipsis concerns the omission of a section of the story that is either obvious enough for the public to fill in or concealed for a narrative purpose, such as suspense or mystery.

Dictionary Definition: ELLIPSIS

The omission from speech or writing of a word or words that are superfluous or able to be understood from contextual clues.

Alfred Hitchcock famously said: “What is drama but life with the dull bits cut out.”

Filmmaking is the representation of life but with the boring parts eliminated. With the goal to enlighten, move, and excite a demanding crowd, films must be stripped from all the “dull bits” that could annoy the spectator.

With the enter-late-leave-early maxim, screenwriters are constantly pressed to pen scripts that don’t include minutia. Suppose a scene opens with a college professor writing on the whiteboard. In that case, the audience will assume that earlier that the day, the instructor got up, had breakfast, brushed his teeth, drove to work, parked the car, greeted his colleagues, went to his classroom, greeted the students, rummaged through his briefcase, and grabbed a marker… There is no need to show the obvious and the tedious. And unless the professor is going to write something important on the whiteboard, starting the scene later in his office during a fit with one of the students would be a better, more exciting opening.

In Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), the movie opens with the protagonist, Cecilia (Mia Farrow), admiring a movie poster. Her morning routine is wholly excluded from the narrative. Breakfast and hygiene are habits practically shared by every character in the movie. But stopping to appreciate a movie poster is pertinent only to Cecilia.

There may be instances in which writers and directors overlook the norm. The editor, then, will have to exert final judgment and decide if a potentially boring scene works or doesn’t.

Parallel Editing

Parallel editing (cross-cutting) alternating between two or more scenes that often happen simultaneously but in different locations. If the scenes are simultaneous, they occasionally culminate in a single place, where the relevant parties confront each other.

The clip below is from The Silence of the Lambs (1991). It is one of the most famous occurrences of cross-cutting in American cinema. It happens in the film’s third act and spoils a big surprise, so if you haven’t seen the movie and if you don’t like spoilers, watch the film first. It is a must-see.

Why use it?

To add interest and excitement to an otherwise boring sequence. Parallel editing is often applied to create suspense. Imagine the following scenario:

A woman takes a shower, singing gaily. Steam fills up the bathroom. Finishing up, she turns off the water. She dons her bathrobe and enters her bedroom. As she opens the closet, a masked assailant stabs her on the stomach.

What’s wrong with the scene? A woman taking a shower, singing, and dressing up is not particularly exciting. How can we improve this scene? With parallel editing. Now imagine this scenario:

A woman takes a shower. A van pulls over in a dark alley. The woman sings gaily. Steam fills up the bathroom. Two masked assailants are in her kitchen. The window behind them is broken – their entrance. The woman turns of the water. One of the assailants yanks a knife out of the holder. The woman dons her bathrobe. The two assailants venture on the second-floor hallway. One of them enters the bedroom, hides in the closet. The woman leaves her bathroom into the room. She opens her closet and is stabbed on the stomach.

Think of visual value. The first version is only exciting at its conclusion when the woman is stabbed. This second version is suspenseful throughout, especially with ominous music. To a savvy filmmaker and cinephile, it’s obvious that the two storylines will intersect in a central plot point.

When use it?

Implement cross-cutting when you’re confident it’s going to work, and you have the budget for it. Notice that in the two versions above the plot point is the same: the woman is stabbed. Everything else is potentially superfluous.

So if you have the budget, shoot both scenes and apply parallel editing. If you don’t have the budget, abridge the shower scene and move to the bedroom and the stabbing as quickly as possible.

The Kuleshov Experiment

At the dawn of the 20th century, cinema was a new art form, comprising many techniques that hadn’t been developed. And the ones that had not been studied to the needed extension. The elements of editing were among them. Filmmakers knew that you could cut and splice the film strip, but they didn’t thoroughly comprehend its purpose.

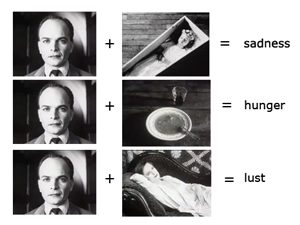

Lev Kuleshov, a Soviet filmmaker, was among the first to dissect the effects of juxtaposition. Through his experiments and research, Kuleshov discovered that depending on how shots are assembled, the audience will attach a specific meaning or emotion to it.

Lev Kuleshov, a Soviet filmmaker, was among the first to dissect the effects of juxtaposition. Through his experiments and research, Kuleshov discovered that depending on how shots are assembled, the audience will attach a specific meaning or emotion to it.

In his experiment, Kuleshov cut an actor with shots of three different subjects: a hot plate of soup, a girl in a coffin, and a pretty woman lying on a couch. The footage of the actor was the same expressionless gaze. Yet the audience raved about his performance, saying he looked hungry, sad, and lustful.

In a 1964 interview for the show Telescope, Alfred Hitchcock called this technique “pure cinematics – the assembly of the film.” Sir Hitchcock says that if a close-up of a man smiling is cut with a shot of a woman playing with a baby, the man is portrayed as “kindly” and “sympathetic.” By the same token, if the same shot of the smiling man is cut with a girl in a bikini, the man is portrayed as “dirty.”

Both these examples further illustrate the power of editors as storytellers. The data gathered with the Kuleshove Experiment were heavily used by Russian filmmakers, especially with respect to the Soviet Montage.

Types of Transitions

In film editing, transition refers to how one shot ends and the next begins and the filmic device that bridges one to the other. Many different types of changes have been employed since the early years of cinema. Some are outdated, used mainly to refer to those first years, but others are still extensively used today. Each type invokes a different emotion. Understanding those emotions is essential to master editing.

Cut

The cut is the most fundamental and popular kind of transition. A cut occurs when one shot immediately follows another. The number of cuts in a typical feature film typically numbers in the thousands.

In particular, as the Kuleshov Experiment showed, cuts are crucial for the effects of juxtaposition. Although most cuts are purely technical, the abrupt switching from one shot to the next frequently necessitates a particular interpretation from the viewer.

Look at the following illustration from Three Days of Condor’s opening (1975). Keep in mind that at this point in the film, Robert Redford’s Joseph Turner, the primary character, has not yet been presented.

The second shot cuts to the exterior of a busy street, showing a man driving a motorcycle.

The clear understanding is that the man on the bike is Turner (mentioned in the first shot) and is riding to work. Though the audience’s assumption may not be correct, the editor must be aware of the implications of how he cuts a scene.

Cuts became the industry standard for two reasons: First, during the early years of cinema, when editing the actual film, the editor could very easily cut the celluloid strip with a blade or scissors and splice it together. Any other type of transition would require further processing from a specialized lab, therefore increasing costs. Second, the different types of transition are more distracting. Cuts allow for a better flow of the movie.

Fade in/out

Fade-ins and fade-outs are the second most common type of transition. Fade-outs happen when the picture is gradually replaced by a black screen or any other solid color. Traditionally, fade-outs have been used to conclude movies. Fade-ins are the opposite: a solid color gradually gives way to a picture, commonly used at the beginning of movies.

Despite being the second most used transition, editors seldom adopt fades. An average feature film will have only a couple of fades if that. Fades are used sparingly because they imply the end of a major story segment. Fades are also utilized when allowing the audience time to catch their breath after an intense sequence. In Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), one fade-out takes place right after Butch (Bruce Willis) rams his car into Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames), an unexpected accident that drastically alters the lives of those two characters.

Dissolve

Also known as overlapping, dissolves happens when one shot gradually replaces by the next. One disappears as the following appears. For a few seconds, they overlap, and both are visible. Commonly used to signify the passage of time.

Wipe

Wipes are dynamic. They happen when one shot pushes the other off the frame. George Lucas deliberately used them throughout the Star Wars series.

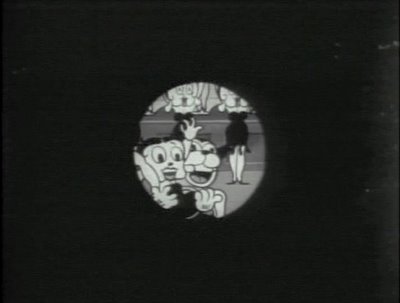

Iris

The iris is an old-fashioned transition hardly employed today when circular masking closes the picture to a black screen. Irises are found in some cartoons like this example from Betty Boop:

Nowadays, editing programs have introduced several other types of irises, like a star or heart. Though they have no place in serious filmmaking, they are great tools for homemade videos.

Montage

A montage is “a single pictorial composition made by juxtaposing or superimposing many pictures or designs.” In filmmaking, a montage is an editing technique in which shots are juxtaposed in a fast-paced fashion that compresses time and conveys a lot of information in a relatively short period.

Two Contrasting Examples

The two clips below epitomize what a montage consists of. I chose these particular examples because they are from major motion pictures, and both illustrate the same topic – a trip – but in two extremely contrasting ways.

The montage from 1969 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid shows a trip from New York City to Bolivia that occurred at the beginning of the century. The second montage is from 2002, The Rules of Attraction, narrating a journey across many European countries.

The 33-year time gap between both movies is evidence of how styles change over time, especially as they tell stories that took place a hundred years apart (Butch Cassidy traveled to South America in 1901.)

What to Avoid

Montages cannot create strong emotions. Ergo, they are not used to make the audience feel, rather they make the audience know. Montages inform.

This is so true that simple text cards could replace the message inherent to some montages. However, this alternative is far less exciting and stimulating… far less cinematic. Think of Rocky (1976) and the now famous training montage. That whole sequence could be replaced by a title card reading “After weeks of training, Rocky improved his stamina and perfected his boxing skills.” This short sentence summarizes that 3-minute montage… but which one do you think is more cinematic? Which one would make you have goosebumps?

For this reason, it is often said that characters cannot fall in love during montages. The courtship and romance would be too bland or dull. Love deserves better treatment.

Be First to Comment