Many critics have argued convincingly that film noir follows much the same pattern of rewarding “good” women and punishing “bad” women as conventional Hollywood films. The rewards and punishments for women (and men) in film noir are especially serious — characters who willingly play their proper roles tend to survive beyond the end of the film, while characters who resist playing these roles often die violently or, less commonly, go to jail. On rare occasions, these films even deliver a Hollywood happy ending, when a family or a relationship that was threatened or torn apart during the course of the film actually is restored in the final scene. Meanwhile, critics who find a conservative message in film noir point out that these films endorse the family not only in their narrative content but even in their visual style, which creates a negative contrast between the noir world and the world of traditional family life.

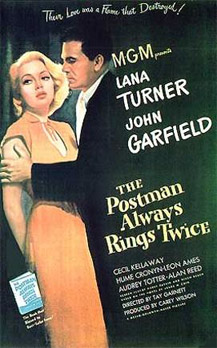

Claire Johnston argues that film noir reinforces the male-dominated status quo family by destroying characters who threaten the established order — particularly women. She points out that noir films like Double Indemnity (1944) often depict transgressions against the family that involves a discontented wife who murders her husband. But rather than casting doubt on the traditional nuclear family, these female transgressors exist only to be beaten down and destroyed. This pattern is repeated in classics of film noir such as The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), Out of the Past (1947), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), and Dead Reckoning (1947). The wife who achieves independence through murder inevitably dies violently — sentenced to death by a film that supports the status quo as represented by the law against murder. Film noir, therefore, provides an affirmation of the dominant social order and a warning against disturbing it:

“Far from opening up social contradictions, the [detective] genre as a whole . . . performs a profoundly confirmatory function for the reader, both revealing and simultaneously eliminating the problematic aspects of social reality by the assertion of the unproblematic nature of the Law.” 19

Janey Place agrees that film noir tends to destroy the independent woman as a moral lesson to the audience and to the male characters who fall under her spell:

“The ideological operation of the myth (the absolute necessity of controlling the strong, sexual woman) is thus achieved by first demonstrating her dangerous power and its frightening results, then destroying it.” 20

This view of film noir emphasizes the danger that independent women represent for men by tempting them to venture beyond the safety of the family, if only temporarily. Women in film noir tend to express their independence in sexual terms — they use their sexuality to manipulate men, rather than submitting it to the moral code of a traditional family and the control of a husband. Their sexual independence threatens the men and the family relationships around them by providing a dangerous alternative to the traditional family unit. The sexually independent woman serves to reinforce the status quo family because it is through her that the hero learns his “proper place.” Thus, in a film such as Pitfall (1948), according to Nina Leibman, the errant husband learns that the only appropriate and indeed safe place for a man or a woman is the nuclear family:

John is bored and cynical about his family life and is looking for excitement. It is John’s search for adventure outside the socially approved realm of his family that leads to his relationship with Mona and ultimate danger. . . . Because John dares to criticize the socially approved family unit, because he transgresses the boundaries of such an ideal enclave, he is punished. 21

The same lesson can be found in D.O.A. (1950), a film in which the hero’s attempt to escape from a family relationship leads to even graver consequences. Frank Bigelow (Edmond O’Brien) takes an out-of-town vacation in order to break free of his fiancée’s grasp and to have one last sexual fling, but soon learns that he has been “murdered” with a dose of incurable poison. Deborah Thomas notes that the film makes a clear connection between Bigelow’s infidelity and his “murder” — his rejection of marriage leads directly to his death: “Significantly, it is while Frank was trying to pick up another woman in a bar that the poisoned drink . . . has been substituted for his own.” 22

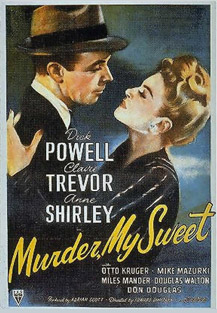

Although the characters of film noir often are doomed to suffer severe punishment for their nontraditional behavior, a significant number of noir films might appear to take a different approach to reinforce the status quo. These films borrow their endings from conventional Hollywood melodrama and romance by allowing the hero and his love interest to overcome obstacles to their relationship and emerge from the noir world into the world of successful marriage and family life. This type of conventional “happy ending” occurs in such noir classics as Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), I Wake Up Screaming (1941), Laura (1944), Murder, My Sweet (1944), Gilda (1946), The Big Sleep (1946), The Lady in the Lake (1947), and Dark Passage (1947).

Noir films’ visual representation of these characters and their surroundings also can be interpreted to show support for the nuclear family and disapproval of independent women and unsatisfied husbands. Traditional women typically appear in daylight or high-key lighting, exist outside of the city’s corruption and danger, and live contentedly in the family home. In contrast, the anti-traditional femme fatale, according to Janey Place, “is comfortable in the world of cheap dives, shadowy doorways, and mysterious settings.” 23

Nina Leibman writes that noir films such as Pitfall and The Big Heat endorse the traditional family by creating a visual distinction between the world of the family home and the noir world outside:

The mise-en-scène displays open doorways, neatly stacked dishes in glass cabinets, kitchens with talkover counters, a charming child’s room. The characters interact with the domestic items in a familiar, contented manner.

. . . The nuclear family is reinforced as ideal by the films’ visual preference of the suburban home as well as the negative repercussions that befall those who express unhappiness with or neglect of the nuclear unit. 24

WOMEN’S ANTI-FAMILY FUNCTION IN FILM NOIR

The explicit messages of film noir seem to be clear regarding women and the family: Women who transgress the boundaries of conventional family life meet with and deserve the most extreme punishment, and the men who fall victim to their sexual charms meet a similar fate.

Characters who resist or threaten the nuclear family becomes trapped in the noir world, which is abnormal, dark, dangerous, and incompatible with traditional family values. The family home and the women who choose to live there in their proper place appear as ideals or models of correct behavior. But beyond the more explicit lessons and images lies a much different interpretation of film noir and the function of women in these films. Women in film noir do not merely provide a variation on the pro-family theme of contemporary Hollywood films — rather, they reveal a distinctly anti-family current running just beneath the surface of noir films. This barely hidden message, according to Sylvia Harvey, never amounts to an all-out attack on the status quo family, but it exists nonetheless: “[T]he kinds of tension characteristic of the portrayal of the family in these films suggests the beginnings of an attack on the dominant social values normally expressed through the representation of the family.”25

Critics tend to classify the women of film noir into two categories identified by Janey Place: the “rejuvenating redeemer” or “good” woman and the “spider woman” or femme fatale. But noir films also feature a third type of female character, the “marrying type” — a woman who poses a threat to the hero by pressuring him to marry her and “settle down” into his traditional role as breadwinner, husband, and father. These women are qualitatively different from the women of classical Hollywood cinema. Perhaps more than any other single element of film noir, the women function as an expression of the films’ underlying skepticism toward the traditional family. Indeed, the three types of female characters are so essential to the meaning of these films and so peculiar to this body of films that they can be seen as part of the iconography of film noir.

Be First to Comment